|

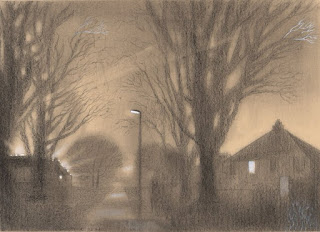

| 'Rhetoric” by EpicTop10.com (CC BY 2.0) |

What do you think of when you hear the word ‘rhetoric’? I asked a few friends and this is what they said:

I think of Cicero and rhetoric — a spoken essay or

persuasive piece. Asking questions without opposition, or without having them answered.

It’s often political, in my opinion. Sounds like a long

speech.

I can see it began with Cicero — this is how you persuaded

people. But when you know the tropes it becomes mere rhetoric. As soon

as the cat’s out of the bag it’s not magic any more.

The word now seems to have a negative feel, perhaps paired

with the words ‘empty’ or, as the third speaker says, ‘mere’. It implies

insincerity. Also, it is often associated with politics, as the second speaker

says. For example, a Spectator article by Kevin Hague in June 2022 on the first

instalment of the Scottish government’s independence prospectus says: ‘Instead of the

robust analysis and sound logical reason we might expect from a paper produced

by Scottish civil servants, we are instead offered pages upon pages of lazy

rhetorical assertion.’

Yet rhetoric was a central part of a young gentleman’s

education from Ancient Greece until the late nineteenth century, and is still taught today. Aristotle laid out the first systematic ground rules. It was a

positive accomplishment, meaning the art of speaking and persuading. It

included a wide range of speaking skills, such as ways of exaggerating or

minimising your points; selecting words and phrases to surprise and delight

your audience; down to well-known epithets like ‘brave soldier’ or ‘sturdy oak’.

|

So it was originally an oral form which moved to writing. Rhetorical devices were catalogued as an aid for writers by critics such as George Puttenham in the sixteenth century, and it was used in poetry, essays and other written genres. To give just one example, literary critic Walter Ong points out that Victorian prose writing drew on the rhetorical virtue of ‘copia’, speaking in abundance, and this to us can seem irritatingly verbose.

Rhetoric on a private level

So how might rhetoric perform not to an audience, but on an individual, private level? This is one of the questions I’ve been thinking about recently while reading sixteenth century poet Philip Sidney’s ‘Astrophil and Stella’, a series of 108 sonnets and 11 songs about unrequited love for the lady Stella. In sonnet 34 Astrophil has a dialogue with an inner critic, who tells him ‘wise men’ will think his complaints about his misery stupid. Then those men shouldn’t tell anyone, Astrophil retorts, and no one will be disappointed. But the inner critic is not happy with this reply — it is stupid to speak without an audience:

What idler thing, then speak and not be heard?

Astrophil replies:

What harder thing than smart, and not to speak?

In other words, if you are hurting, you have to speak, no

matter whether there is an audience or not.

These two lines from the sonnet are both rhetorical

questions in our commonly understood sense, in that they do not require a real

answer. Not only that, but the second question responds to the first by echoing

its rhythms and retorting rather than engaging. The attempted answer is itself

a rhetorical question, batting the ball back to the critic, so to speak.

Much of Astrophil and Stella lies between these two questions

— written from pain out of necessity, but without a defined audience. It is not

clear who the series is written for in fact, and is not writing without an

audience pointless? But feeling without speaking is impossible, says Astrophil

here. So the rhetoric has taken us to a place outside the declamatory structure

of these two questions, to a place created by the tension between them.

Astrophil has not persuaded himself but the sonnet form allows these two

unanswered questions to stand, unresolved.