Revisiting the mosque

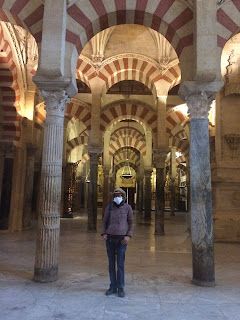

The first time I visited the Grand Mosque in Córdoba, 10

years ago, I was captivated by the generous space inside, divided by corridors of pillars with their famous orange and white double arches. Since

then I have returned to it often in my mind and it has become a visual metaphor

which has helped me at various times.

Mosque or cathedral?

This time, however, I saw it in a different way, noticing

the history and different influences over the centuries which have formed this

building. If there’s anywhere that fits the bill of that now rather bland word

‘contested’, it’s this space. My ticket tells me I’m in a cathedral, and so

does King Juan Carlos on a marble plaque inside, but it’s widely known as the

Grand Mosque.

The history of the mosque

It was originally a mosque, seized in 1236 by Christian

forces. A Catholic nave was inserted in the centre in the 16th century and side

chapels put around the walls. But a plaque in the courtyard says the Grand

Mosque had itself been built on a previous Visigothic Christian site, a sixth

century basilica dedicated to Saint Vincent was whose devotees were ‘dispossessed

of it in the Muslim invasion’. There is not much archaeological evidence for this, although there is a fragment of a Visigothic building from the site displayed

inside the mosque.

There’s lots of writing inside. On the wall of the nave is a plaque (above) with a list of priests who were killed for their faith ‘in the religious persecution of 1936-39’ — eh? Spanish Civil War, surely? Elsewhere are plaster casts of both Arabic and Spanish names which had been cut into the columns as graffiti, perhaps by generations of bored worshippers.

Living together

I hope that this coming together of symbols of two different

religions over time can now be a sign of how people of different religions, or

none, can live together without trying to take vengeance for the injustices of

the past or obliterate evidence of them. So the painting (below) of King Ferdinand receiving

the keys to the city from kneeling vanquished Muslims, crescent moons prominent

on their turbans, I would not remove as an affront to Muslim or postcolonial

sensibilities. I would leave it as important evidence of past events and

attitudes, trusting the present-day public, of whom I am one, to interpret and

understand it according to our now more enlightened views.

Reinterpretation not destruction

So I am against tearing down monuments, even to events we now regard as oppressive and unpleasant or worse. They are evidence of various degrees of conflict, achievement and plain everyday living together. I would reinterpret statues, not reanimate the conflicts they may represent. In other words look forward, not back.